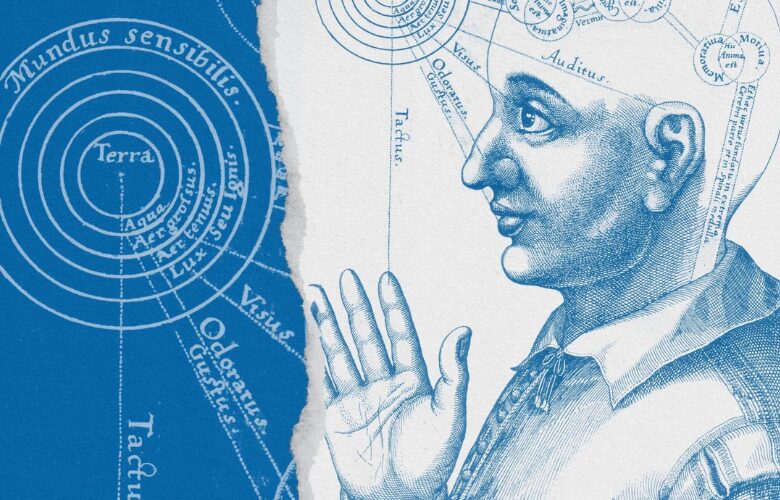

Leadership hinges upon the intricate interplay of human interactions, perceptions, and experiences. In exploring the landscape of effective leadership, the framework of phenomenology resonates with me. Phenomenology unveils the essence of consciousness and the intricate layers of how individuals perceive and engage with their realities.

Within the context of leadership, phenomenology serves as a compelling lens through which to comprehend the intricacies of human behavior, cognition, and the profound influence of subjective experiences on guiding and inspiring others toward collective goals. Its philosophical underpinnings offer valuable insights into leadership dynamics, fostering an understanding of the subjective experiences of those we work with. In this article, I’ll deliberate the historical context of phenomenology and its relevance to leadership, clarifying how this philosophical framework can enhance leadership effectiveness. Before we unearth the history and dissect concepts about it means to be human, you might be wondering what phenomenology is. The term phenomenology emerged in the late nineteenth century and is a philosophical approach that focuses on the study of subjective human experiences and the structures of consciousness.

At its core, phenomenology seeks to understand how individuals perceive, interpret, and experience the world around them. It emphasizes the examination of phenomena as they appear in consciousness, aiming to describe and analyze these experiences without imposing preconceived ideas or interpretations.

Bracketing or Epoché: This method involves suspending or setting aside preconceptions, beliefs, and biases when examining phenomena. By doing so, phenomenologists attempt to approach experiences with fresh and unbiased perspectives. For example, when we see theatre, we suspend our disbelief so that we are able to fully believe the story being told on stage.

Intentionality: Phenomenology explores the intentional nature of consciousness, emphasizing that consciousness is always directed towards something—an object, an experience, a thought, etc. This focus on intentionality highlights the relational aspect between the subject (the experiencer) and the object (that which is experienced).

Lived Experience: Phenomenology places significant importance on the lived experiences of individuals. It acknowledges that our experiences are shaped not only by our thoughts but also by our bodily sensations, emotions, cultural backgrounds, and social contexts.

Eidetic Reduction: This method involves examining the essential or universal aspects of an experience, aiming to uncover its fundamental structures or essences. It seeks to identify the essential characteristics that define a particular experience.

Phenomenology has applications across various disciplines, including philosophy, psychology, sociology, theatre, and even leadership studies. It provides a framework for understanding how individuals perceive and make sense of their realities, shedding light on the subjective nature of human experiences without dismissing their significance in understanding the world.

Phenomenology emerged as a philosophical movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, spearheaded by thinkers like Edmund Husserl and later expanded upon by Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and others. Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, aimed to investigate the structures of consciousness and experience, emphasizing the study of phenomena as they appear to consciousness, devoid of presuppositions and biases.

Heidegger shifted phenomenology’s focus towards the “being-in-the-world” concept, highlighting the interconnectedness between humans and their surroundings. Merleau-Ponty added the dimension of embodiment, emphasizing the significance of the body in shaping our experiences and perceptions. These developments in phenomenology laid the groundwork for understanding how individuals perceive and make sense of the world around them, a fundamental aspect of leadership.

Successful leadership involves complex human interactions, requiring an understanding of diverse perspectives, emotions, and experiences. Phenomenology offers several key insights that can significantly impact leadership effectiveness:

Understanding Subjectivity: Phenomenology emphasizes the importance of acknowledging subjective experiences. In a leadership context, this means recognizing that individuals perceive and interpret situations differently based on their unique backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences. A phenomenologically-informed leader understands that there is no single, objective reality, and instead appreciates the multiplicity of perspectives within our team.

By valuing diverse viewpoints, leaders can foster an inclusive environment where team members feel heard and respected. This understanding allows leaders to encourage open communication, inviting contributions from all team members, thereby promoting creativity and innovation. Moreover, by embracing subjective experiences, we can tailor our approaches, strategies, and communication styles to resonate with different individuals, enhancing team cohesion and productivity.

Embracing Embodied Experiences: Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s emphasis on the body’s role in shaping experiences has profound implications for leadership. Leaders who grasp the significance of embodied experiences recognize that emotions, cultural backgrounds, and physical contexts influence how individuals perceive their work environment and interact with others.

Leadership practices can be adapted to consider these embodied experiences. For instance, understanding that a physically comfortable workspace or accommodating diverse working styles can positively impact productivity and morale. Leaders attuned to the embodied aspects of their team members can create environments that promote well-being, engagement, and a sense of belonging, ultimately fostering higher levels of motivation and commitment.

Phenomenology encourages individuals, including leaders, to suspend assumptions and preconceptions when approaching situations. A phenomenologically informed leader is self-aware, recognizing their own biases and actively seeking to understand how these biases might influence our judgments, decisions, and interactions with others.

By being mindful of biases, we can make more informed and fair decisions, avoiding the pitfalls of unconscious biases that may hinder team dynamics or limit opportunities for certain individuals. This self-reflection enables us to cultivate a culture of openness, where constructive feedback is welcomed and different perspectives are valued, creating an environment conducive to growth and learning for everyone.

Phenomenology encourages authenticity and self-awareness in understanding our own experiences and perceptions. Authentic leaders are genuine and transparent, aligning our actions with our values and principles, which I like to call “living in my values.”

Leaders who adopt these core principles take the time for introspection, examining our motivations and the impact of our decisions on others. This self-reflection allows us to lead with integrity, building trust and rapport with our team members. Authentic leaders create an atmosphere of trust and psychological safety, empowering our teams to take risks, innovate, and contribute meaningfully.

Phenomenology’s exploration of consciousness, subjectivity, and lived experiences offers a rich framework for understanding the complexities of human interactions, making it highly relevant to leadership. By embracing phenomenological principles, leaders can cultivate empathy, inclusivity, and authenticity, fostering environments conducive to collaboration, innovation, and growth within their teams and organizations.

Also by Bryan Runion:

The Art of Stage Management: Blending Education and Experience

Bryan Runion is a professional Production Stage Manager whose credits include: Drawn to Life (Cirque du Soleil and Disney), Netflix’s Stranger Things: The Experience, Duel Reality (7 Fingers), La Perle (Dragone), The Voice of Tolerance (The Ministry of Education, UAE); Mastercard Experiences (Mastercard); Everybody Black (World Premiere), Queens (La Jolla Playhouse), Ken Ludwig’s The Gods of Comedy (The Old Globe), TEDx (Chula Vista), Mark Morris Dance Company, Joey Alexander Trio, Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain (La Jolla Music Society), The Bridges of Madison County (Arkansas Rep). Bryan earn his M.F.A. at The University of California, San Diego and his B.A. at The University of Arkansas at Little Rock. He is a proud member of Actors’ Equity Association and The Stage Managers’ Association.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.