If this is the year you’re going to take the plunge into podcasting, then here are a few tips I wish I had known when I first started. Many of the engineers I know in podcasting came from music or theater or production backgrounds, so it’s not unheard of to make the switch. You already know the basics of audio, so there’s tons of overlap, but there is quite a bit you need to pay attention to when working with the voice.

Two-ways are just interviews. A host and a guest. Maybe some music.

Narrative or long-form are usually documentary-style meaning you’ll have a narrator telling the story along with voices from interview subjects. The interviewee’s soundbites are cut into what’s called selects and usually edited to fit the narration. These are scripted and will normally have scoring as well as sound effects.

Non-narrated podcasts have an interview subject telling their own story edited together with music. (Something like Song-Exploder might be a good example here)

On each individual track, I usually have an EQ, a compressor, an expander, a de-esser, and Izotope’s Mouth De-click. On each individual track, I use LIGHT compression – you want some compression because otherwise you’re going through a ton of small tiny bits of audio and adjusting each level and that will get tedious. But you don’t want to over-compress because the voice will sound unnatural. Expanders help get rid of any unwanted studio noise, but again I use light settings here. And you’ll have to play with your de-esser to find the right settings here.

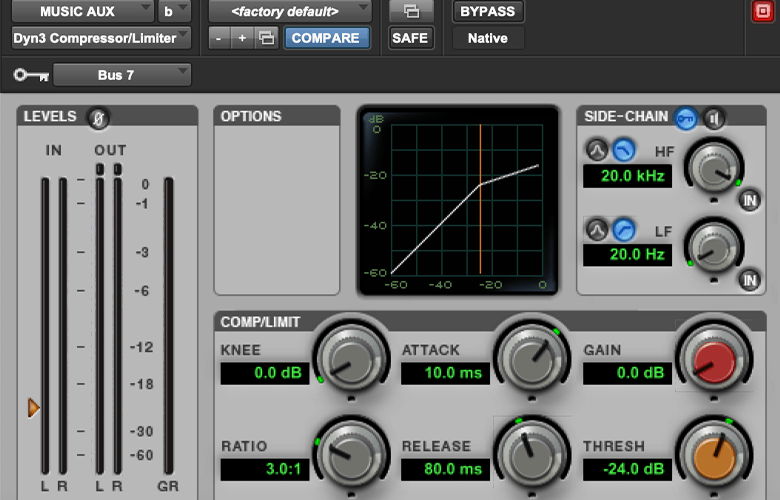

On my VO aux, I have something similar. An EQ, a compressor, an expander. This allows me to set an overall EQ to ALL my VO together to give the podcast some uniformity but also allows me to manipulate the level of my VO in relation to the music and the sound effects. If you have a narrative podcast with something like 20 different tracks, having control of things with one aux is very helpful. I tend to err on light compression and expansion overall but depends on what kinds of voices I’m working with.

My music aux may or may not have light compression, but it does have EQ. Sometimes, I have a sidechain into my compressor that’s being fed by my VO aux. So my compressor will kick in when the voice comes in. This isn’t always necessary, but I’ve found I like it so the music isn’t always being compressed. For me, my main goal with the music aux is just to be able to manipulate as a whole. When you start getting into heavy automation within a podcast, it can get annoying to adjust that track by 1 dB and screw up your automation.

SFX aux is similar, for me it’s mainly level control.

My master usually has a limiter and a meter of some sort. I use Izotope Insight for metering and am usually mixing to -16 LUFS but it depends on who you’re mixing for. Broadcast standards can be -24 LUFS.

Because podcasting is all about the story being told, you want to make sure that the voice is the most prominent and important thing you’re hearing. This is why having auxes can be such a lifesaver.

You will want to take one initial pass through the edit sent to you that will be just to adjust levels and deal with any big issues. These can be things like buzz, noises, plosives, and other random things that can happen. I don’t work for Izotope, but they are great and have some of the best denoising plugins around. Vocal denoise, mouth declick, EQ match, deplosive, dewind, so many different things you can do to clean up the audio. During the pandemic, the audio quality has suffered a lot since people are recording anywhere and with anything. So, whether it’s Izotope or Waves denoising or whatever other tools you can get your hands on, get to know them, and know how to use them.

The most important thing with podcasting is paying attention to detail. Make sure you don’t cut off breaths but do cut off stutters or any fumbles. Don’t listen too loud, but make sure you listen at a level that you can hear if you cut off a breath! Pacing is important. Make sure the VO isn’t going too fast or slow. Enjoy the story you’re being told. Try to make sure the music is adding to that story and not detracting from it. And if you’re working with a script and something is off, make sure to check with your producer because they may have missed something.

Once you feel you’ve gone through your mix a few times, and you feel confident it’s ready to go, a good rule of thumb after bouncing is to re-import to your session and analyze the audio to make sure you’re at the correct levels. Also, make sure you didn’t cut off the beginning or the end.

Always give your work a final listen, so whether it’s right before you bounce or a quality control after you bounce, just make sure you listen. Podcasts can be long and tedious, so it’s easy for things to slip through the cracks. A 45-minute podcast can take anywhere from 4-6 hours to mix (or more if the audio is particularly bad). That’s just for a 2-way, narrative podcasts can take so much more. But if you pay attention to the details and deliver good work, you can get A LOT of work.

Garam Anday and Pakistan’s Emerging Feminist Punk Scene

The mission of SoundGirls.org is to inspire and empower the next generation of women in audio. Our mission is to create a supportive community for women in audio and music production, providing the tools, knowledge, and support to further their careers. SoundGirls.Org was formed in 2013 by veteran live sound engineers Karrie Keyes and Michelle Sabolchick Pettinato and operates under the Fiscal Sponsorship of The California Women’s Music Festival, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization. In 2012, Karrie and Michelle participated in the “Women of Professional Concert Sound” panel at the AES Conference in San Francisco. The panel was hosted by the Women’s Audio Mission (WAM) and moderated by WAM founder Terri Winston. Terri brought together five women working in live and broadcast audio. The groundbreaking panel (which also included Jeri Palumbo, Claudia Engelhart and Deanne Franklin), provided young women and men a glimpse into life on the road, tips and advice, and a Q & A with the panelists. More importantly though, was how incredibly powerful the experience was for the panelists. We had all been in the business for 20 years or more, yet most of us had never met before that day and within minutes we bonded like long-lost sisters. We were struck by how similar our experiences, work ethics, and passions were and wondered why our paths had never crossed and how our careers would have been different had we been there to support each other through the years. Each of us are strong on our own, but together we were even stronger and a powerful force. We were empowered. Each of us had been asked hundreds of times in our careers: Are there other women doing sound? How did you get into sound? How would a young woman go about getting into sound? Through creating SoundGirls.Org, we hope to establish a place for women working in professional audio to come for support and advice, to share our success and failures, our joys and frustrations, and for empowerment and inspiration.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.