Many believe that in the early days of theatre it was mostly sailors who functioned as stagehands and riggers. While they were on shore leave, or once they were retired. The legends go that in London, for example, there were even underground passages leading directly from the docks to the big theatre venues in town. The sailors ran from the ship to there, did their duties in the theatre, got drunk after, and went back to their ships in the early morning.

I’ve always wondered to which extent these rather nostalgic and adventurous stories are true. Being quite a romantic, I can easily imagine those sailors. And I like the idea of them bringing their rigging skills, terms, and tools to our world of entertainment.

Still, I could not shake the thought of these stories simply being urban legends and began researching online.

It’s an excellent historical deep dive into rigging history and a highly recommended read. I was particularly interested in chapter three: The Myth of the Sailor Stagehand and will love to sum up some of the insights I’ve gathered from this chapter for you in this article.

Over the decades, many encyclopedias, in printed form or on the internet, have agreed that stage rigging has a long nautical tradition. Boychuk names several sources, but let me just quote the most recent one here, Wikipedia:

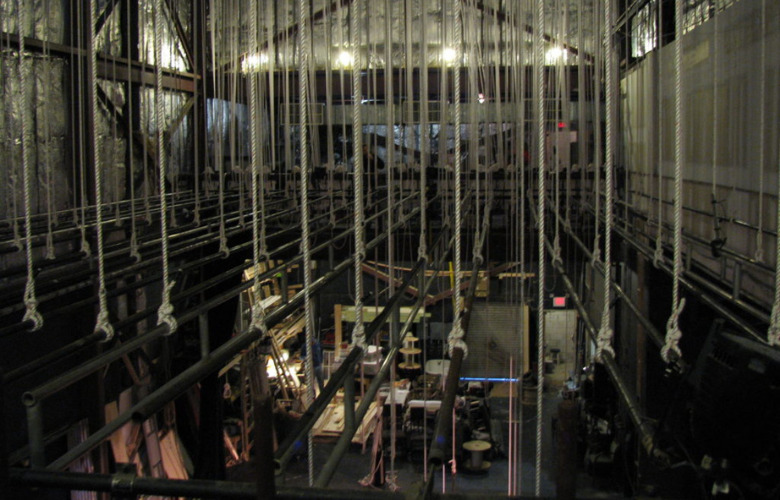

“Stage rigging techniques draw largely from ship rigging. That origin is most obvious with hemp rigging, which uses closely related technology and terminology. To this day, the stage is referred to as a ‘deck’ in the manner of a ship’s deck. Other expressions and technology that overlap the nautical and theatrical rigging worlds include batten, belay, block, bo’sun, cleat, clew, crew, hitch, lanyard, pin rail, purchase, trapeze, and trim.”

Boychuk argues theatre terminology might be misleading. The word ‘deck’, for example could originate rather from the late Middle English ‘dec’, which means covering, roof, cloak and from the Middle Dutch ‘dekken’ which means “to cover.”

As another example, Boychuk researches the term ‘pin rail’ which is often used as proof of a nautical rigging heritage in theatre. Yet no pin rails can be found in old theatres in Europe, the birthplace of modern theatre. What can be found are cleat rails which are not nautical.

In his research, Boychuk found no writing from the 19th century, whether European or North American, that refers to nautical rigging. It all refers to machinery instead.

“The machinery used to fly soft goods was called ‘upper machinery.’ The machinery used below deck was called ‘under machinery.’ The person charged with designing, making and installing the machinery was the ‘stage machinist’.”

“The use of the word rigging is recent. A date for the beginning of the use of the word has not been determined. It doesn’t appear in the Clancy catalogue (a distributor of backstage supplies) until 1904 on page 14 of the catalogue, where it offers ‘Curtain Rigging’.”

Boychuk argues that many researchers and writers over the decades implied nautical heritage. So, an urban myth was born and there is no concrete proof that sailors and ships’ paraphernalia really made their way backstage.

“In the Paris Opera House ‘au cour’ and ‘au jardin’ were used by the technicians to distinguish the sides of the stage. ‘Au cour’ was the side of the stage with the court palace on that side of the theatre building. ‘Au jardin’ was the stage side with a garden on that side of the building.”

“The English of the 19th century had P. and O.P. – prompt and opposite prompt for right and left of the stage. And in North America we have stage right and stage left.”

“If we had a profound nautical tradition, why didn’t we use ‘port’ and ‘starboard’ in our nomenclature?”

Boychuk also points out that most sailors would never have had the energy to work backstage in hard manual labor after and in between their already rigorous workload onboard their ships.

“Most of the sailors – from the beginnings of seafaring until after the Napoleonic wars – perished at sea. The twin scourges of scurvy and the rigor of the nautical life took an extremely high toll.”

“The point is that sailors did not find the time to work backstage in between grueling contracts. They did not retire to a happy life aloft in the theatre. In fact, they did not retire at all. Statistically, they died at sea. Only after the British Navy matured, in the mid-19th century, did any expectation of retirement develop.”

Boychuk supposes that sailors came to the theatre a lot later, at the beginning of the steam ship era. And that maybe then some of them ended up working backstage in theatre because they were used to working at heights.

Maybe, they even brought some jargon with them, but they did not lay the foundations of stage rigging practice as many of us chose to believe.

If you are interested in R.W. Boychuk’s entire, very well researched, detailed chapter, The Myth of the Sailor Stagehand, you can find it here.

The book Nobody Looks Up: The History of the Counterweight Rigging System: 1500 to 1925 can be found on Amazon.

More information about the book also on Goodreads.

Claire Bournet and ‘Trafic de Styles’ in Paris – an Interview

Guilherme Botelho – Dance and the Quest for Meaning

Liam Klenk was born in Central Europe and has since lived on four continents. Liam has always been engaged in creative pursuits, ranging from photography and graphic design, to writing short stories and poetry, to working in theatre and shows. In 2016, Liam published his first book and memoir, 'Paralian'.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.