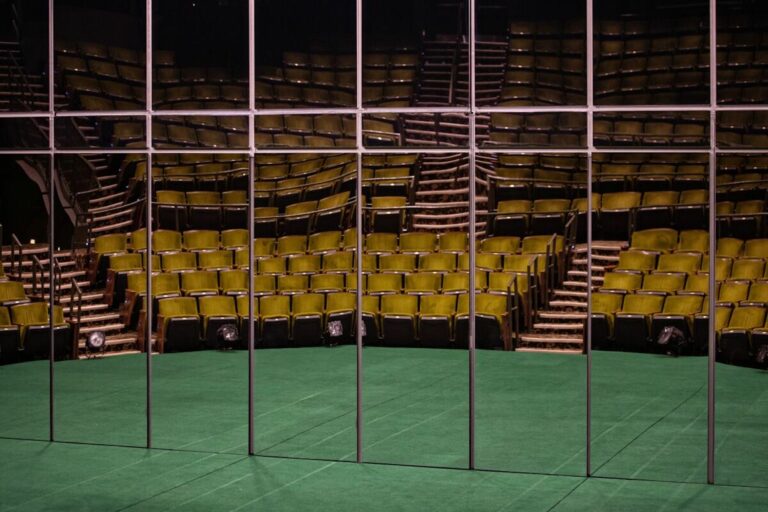

So many articles have come out lately exclaiming the crisis in American theater, with regional theaters shortening or canceling their seasons, while some have closed their doors altogether. And the cause is most often attributed to the pandemic. As an actor and avid theatergoer, it is certainly disheartening for me to witness the impact of financial concerns on theaters, which have long been the heartbeat of our arts communities.

Even major institutions from coast to coast have struggled to survive, leaving them with no choice but to pause programming in 2023.

Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles is facing an $8 million deficit this year, the historic Lookingglass Theatre in Chicago has announced that it would be laying off 50% of its staff, and New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music has fared slightly better, having to reduce its staff by only 13%.

I argue that this American theater crisis is not a creation of the pandemic, but rather an unveiling of pre-existing issues within the theater system. Back in 1998 Richard Hornby wrote “Crisis in the American Theatre” for the Hudson Review, and in it he said, “Broadway is now all but dead; there will always be a Broadway theatre, just as there will always be a New York subway system, but both have become erratic, expensive, and sluggish.” Much the same can be said of regional theatre across the country.

While the pandemic certainly exacerbated the challenges, it actually serves as a mirror reflecting deeper-rooted problems that have been plaguing the industry for years, especially regional and non-profit theaters. From decreasing donations and attendance rates to rising production costs, the pandemic’s aftermath has laid bare the vulnerabilities that theaters were already facing.

“These challenges existed before the pandemic, but not at such an extreme level,” says Teresa Eyring, executive director and CEO of the Theatre Communications Group.

Those season cancellations and layoffs are not isolated incidents. They are symptoms of systemic issues that have been brewing for some time. Before the pandemic, many theaters were programming significantly fewer shows, signaling a shrinking field. Even the federal pandemic-era aid, while providing temporary relief, couldn’t mend the structural vulnerabilities of the theater system. Many theaters had been heavily reliant on donated income for decades, and the decline in contributions left them financially precarious. The shrinking number of subscribers and the unpredictability of single-ticket buyers further exacerbated the challenges. I have spoken with producers here in New York City, who say that people don’t buy tickets weeks or months ahead of time like they used to. Now, it’s more like a few days to even the day of, before audiences finally buy those tickets, so planning ahead and certainty of sales has greatly reduced for many shows on and off Broadway.

Labor market issues, demands for equitable pay, and inflation have put a strain on already tight budgets. But again, this is nothing new, each of these factors have been with us before, leading places like Westport Country Playhouse and California Shakespeare Theater to run emergency fundraising campaigns just to stay afloat this season.

This latest crisis in American theater has only highlighted the need for theaters to adapt and find innovative solutions. Collaborative efforts and co-productions have emerged as avenues to share costs and resources. However, despite these adaptive efforts, fundamental issues remain unresolved. The declining interest in theater among audiences, especially younger generations, is indicative of a disconnect between programming choices and audience preferences. Some theaters have simply forgotten what audiences want. Instead, they alienate audiences by producing shows that are too gloomy or cynical or delve into politically divisive topics. Timothy J. Evans, executive director of Northlight Theater in Skokie, Illinois admits, “They want to laugh and to be joyful and to cry, but sometimes we push them too far.”

Many theaters are discovering the right balance on a show by show basis. Kansas City Repertory Theater presented Ms. Holmes & Ms. Watson — Apt. 2B last year, which is a new Sherlock Holmes-themed comedy written by Kate Hamill and its box office gross greatly exceeded their expectations. Yet their subsequent production of the award-winning play The Royale, written by TV screenwriter Marco Ramirez (Orange is the New Black, Daredevil) about a black boxer who confronts racism in the Jim Crow era, hardly sold any tickets. Similarly, Pasadena Playhouse presented a series of Sondheim-related shows to great success, but then couldn’t get audiences to even notice their production of the immigration-themed Sanctuary City by Martyna Majok.

My point is not that theaters should veer away from difficult or even controversial subject matter, but rather they need to be more strategic and engaged with their audience base to make better financial and artistic decisions. The pandemic was and remains a difficult moment for theaters, but the recovery of American theater requires a collective effort to address the systemic challenges head-on. It demands a reevaluation of funding patterns, programming choices, and community engagement strategies. As Taibi Magar, one of two artistic directors at Philadelphia Theater Company, says, “This art form is thousands of years old, and it has survived so many terrible moments. It will move and morph into its next phase.”

Patrick Oliver Jones has been in the performing arts both onscreen and onstage for more than 30 years. Originally from Birmingham, Alabama, he brought his Southern charm and hospitality to New York City where credits include off-Broadway world premieres and classic musicals. He was in the original casts of First Wives Club in Chicago and two North American tours, The Addams Family and Evita. He has also been recognized regionally for such roles as Bruce in Fun Home (Henry Award nominee for Best Leading Actor in a Musical) and Bela Zangler in Crazy for You (SALT Award Nominee for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Musical). On camera, there have been numerous national commercial appearances (including voiceover work) and co-starring roles on primetime television dramas like Blue Bloods and Law & Order: Criminal Intent. As a producer, Patrick has two shows on the Broadway Podcast Network: Why I’ll Never Make It, now in its seventh season, and Closing Night, and new theater history podcast. In 2022, he received the Communicator Award of Distinction from the Academy of Interactive and Visual Arts for his work in podcasting. His producing efforts also include projects for the stage at various off-Broadway spaces, theater festivals, and concert venues.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.