Music is food for the soul – Arthur Schopenhauer

Music is a moral law that gives wings to the mind – Plato

Music is what gives us memories – Stevie Wonder

Music is the greatest communication in the world – Lou Rawls

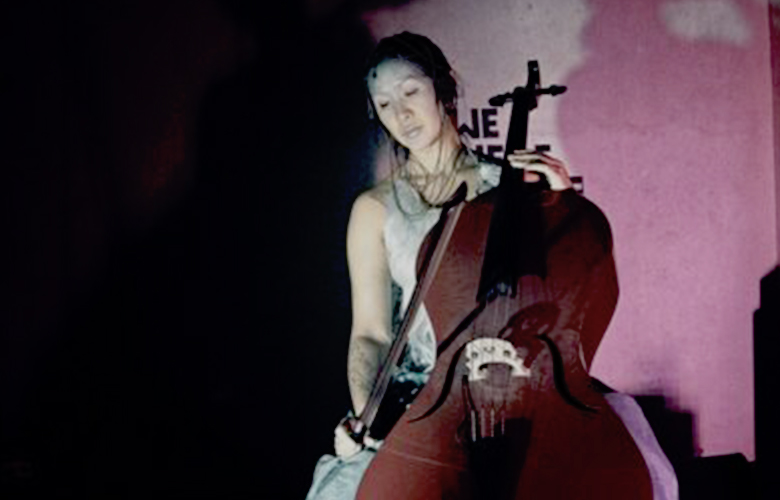

“Music is this awesome, abstract place where your mind ends up!” declares Australian composer Lihla in a burst of contagious laughter. One can easily forget that she is talking about an object when describing her relationship with her cello, a rather large instrument that entirely hid the tiny daughter of Malaysian ancestry when she picked it over violin at age 6! “I’d already been playing piano for three years because taking piano or violin lessons at three years old is just what Chinese kids do, but my relation to the cello is a much deeper one. It is my voice and I’m frankly far more comfortable using its strings than my vocals! It is a very expressive instrument and has such a huge range! It can be so high, go very deep, scream, and allow you to hit those great notes while being a little sexy and very feminine. No other instrument makes me feel this way nor allows me to compose straight from such deep places like this one does.”

The artist quickly draws a fine line between songwriting, which exists on its own, and composing, that relies on collaborations, whether it’s with a movie director, a physical performer or a creative team. A difference that became clear when the Melbourne Conservatory of Classical Music and Victoria College of the Arts’ alumna went on composing for dance companies and circus productions around the world. Musicians and their voices are not the main focus in these creative contexts where songs are forming a soundtrack that has different “what makes it good” criteria from your regular studio album.

The 38 years old laughs again when asked about a composer’s typical schedule: half of the time is spent composing and the other half is about playing and performing those compositions! Pushed onto a path that revolves around the latter once by her college cello teacher, she could easily have winded up a soloist in Philharmonic and symphonic orchestras hadn’t it been for an inspired group of people whose improvisation skills ignited something new in her.

“In this music form, unlike regimented classical music, there suddenly was lots of room for interpretation. Even though I’ve had heated arguments on that topic, I had to admit that I did not like being told what to do, nor wanted to play music the way people expected me to. I kind of fell out of love with classical music. I really rediscovered my musician self through improvisation and electronics!”

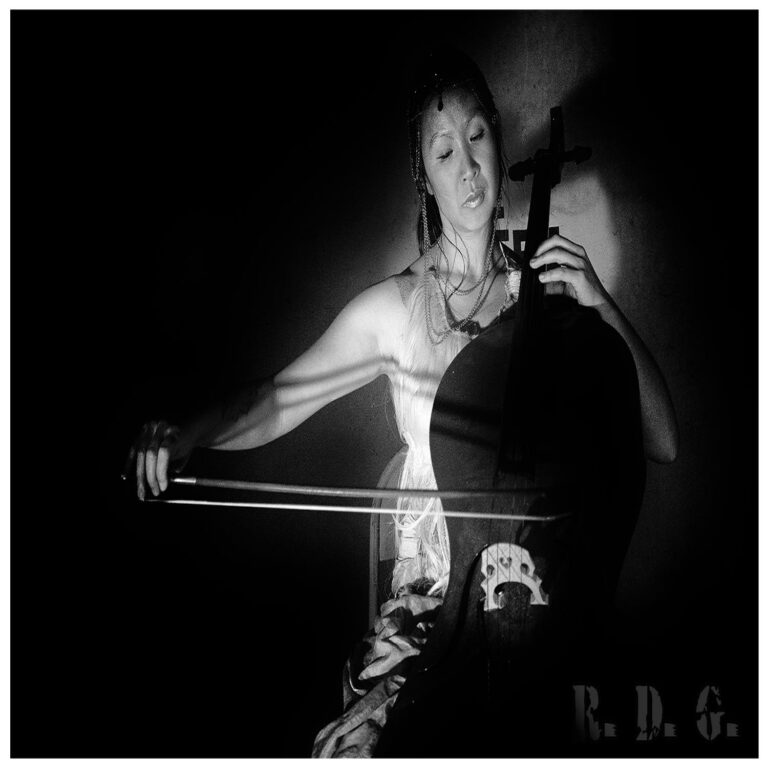

Photo Credit: Reinhard Künstler

Photo Credit: Reinhard KünstlerAs for the difference between stage musician and composer, the Melbourne-born artist laughs before stating how notable and appreciated the absence of her ego feels when composing. Being in a creator’s position rather than a performer’s allows the composer to be sound instead of a person, to explore a marvelously rich spectrum of frequency, space, and time…

Time. Time and time again. This term keeps coming back: how much creation time does the composer get? In what time period is the show set? How long shall the piece last? Are those few hours where my daughter is at daycare enough time to complete those drafts and is it the right time to send them?

“It is all a matter of time! That’s what composing is and my relation to it is very different, whether I’m writing for myself or for others: I don’t care how long the track is when it’s for me! There is no ‘hurry there!’ or ‘maybe stretch this one out…’ Dance pieces and circus acts have an average length of four to six minutes, accents to hit, momentums to build, skills to highlight. Those time restrictions and guide-rules never come up when it’s just my cello and I. Writing is time-consuming and requires discipline, a skill that every composer must have. But composing also just comes when it comes, when the time is right. You cannot force it. I just have to go when it hits me!”

Just a few of the many questions that come into play before the musical creative process has even begun! “And, again, given the importance of time, I cannot get on board too early! A director or any other client who is very clear about what they want can tremendously help a composer deliver tracks early. People who don’t trust their instinct or have too many options in a creative context will often lead to wastes of precious time. I also need some form of a concept, a feeling to get in good improv mode as some of my best comes out of improvisational work, if not by accident!”

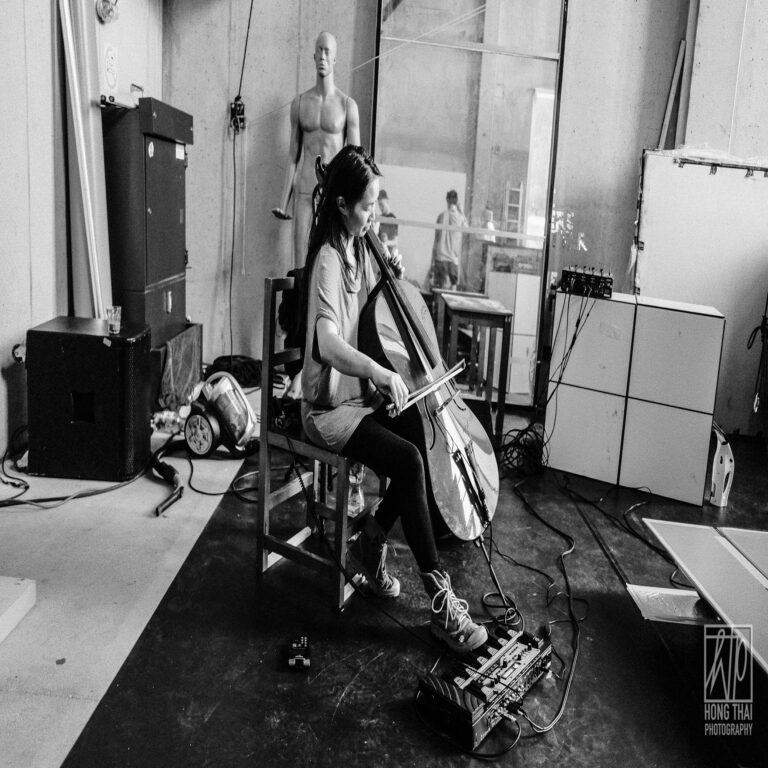

Photo Credit: Reinhard Künstler

Photo Credit: Reinhard Künstler18 years in the music industry, eight of which as a composer, still won’t give you the secret of a good song, of what makes an earworm! “If I knew, I would write commercial music and make a fortune! As for my own pieces, I know that I’m on the right track when the music stays on my mind since I usually have no recollection of what I’ve done after a composing session! That is partly why vocals can be tricky or misleading for a musician as we’ll always be drawn to voice as humans, hence vocals can easily take over and make you forget about the music.”

“All very different creations where my main source of inspiration remained the same: The artists’ presence, the way that each related to the music, and connected with the musicians on stage. No big tricks will move nor inspire me as much as an artist’s presence and musicality. There is nothing harder than writing for someone who has a complete lack of musicality.”

And on that note, Lihla retreats to what she calls her “secret bubbles.” A little studio filled with light on her building’s sixth floor where she finds the peace and quietness, vital to every composer, to write Ambedo, released in 2018.

Also by Martin Frenette:

12 Going on 38: Reprising A Role by Elena Lev

Father And Performer: Two Sides of One Character

Impassioned by performing arts, Martin Frenette started intensive dance training at a very young age before trading pliés and barres for ropes and somersaults at Montreal's National Circus School. He has spent a decade in Europe, performing in various productions. Circus Monti, Chamäleon Theater, Wintergarten Varieté, Cirque Bouffon, GOP Show Concepts, and the Friedrichsbau Varieté have allowed him to grow artistically and humanly. Martin has also invested time working as an artistic consultant, director, and choreographer for both circus and dance projects. He enjoys splitting his time between Europe, Canada, and the US, working on stage and creating for others. Writing has always been a big passion of his and he's thrilled to share his views on shows, the stage, and what's going on behind the scenes with other performing arts enthusiasts!

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.