Have you ever had a little voice in your head whispering that you don’t know what you’re doing? Ever looked around the room with a sinking feeling that you’re the least qualified person there? In small doses, these impulses can push us to improve, to get help and learn from those who’ve come before us. However, when that mentality seeps into our lives and latches on for months, years, or even decades, we find ourselves faced with the far more problematic Imposter Syndrome.

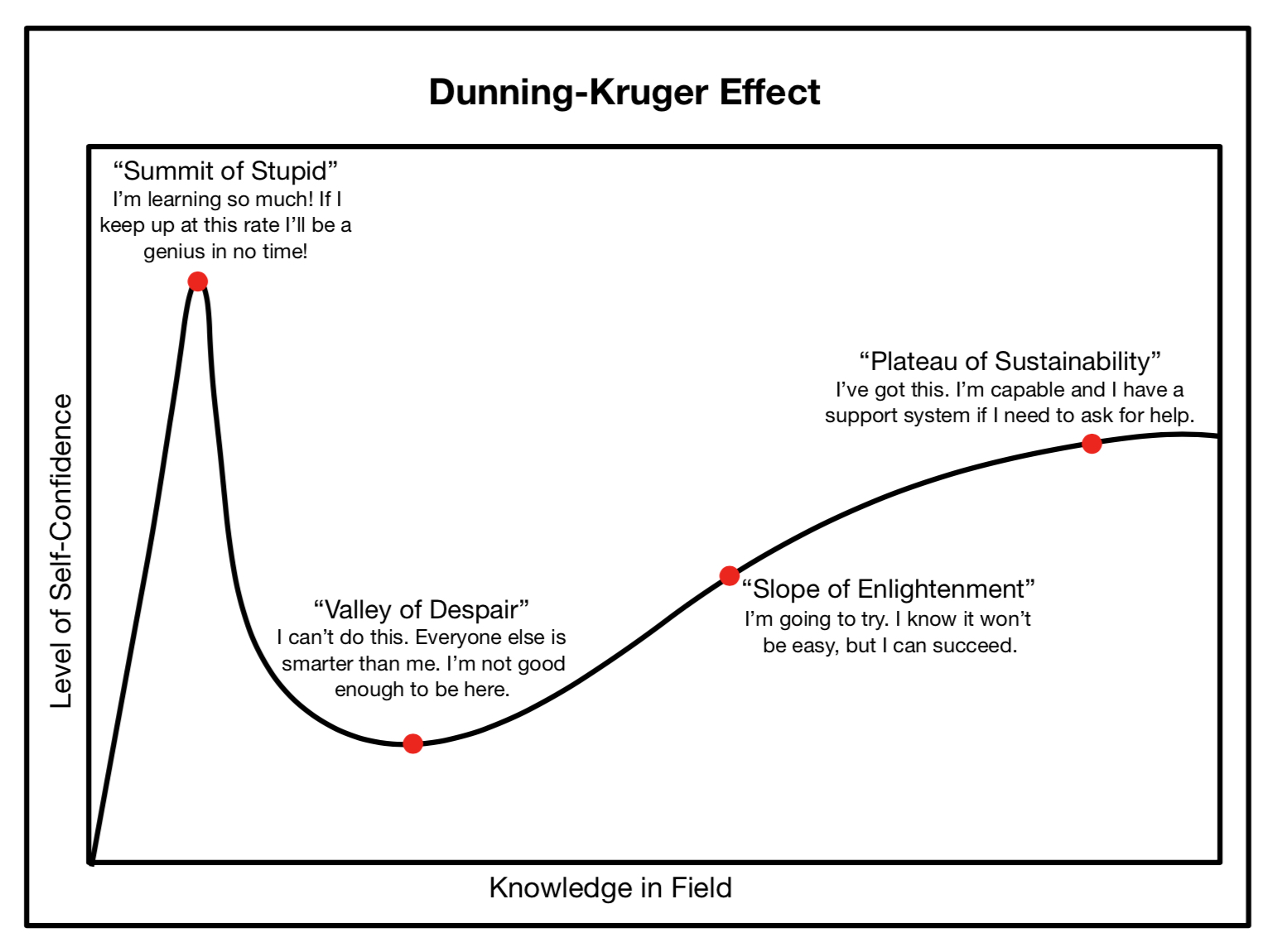

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is the best representation I’ve found to conceptualize the progression that most people follow during their careers. As you can see, it’s not a linear road to travel, even in its most simplified form. As 2021 continues, and we hopefully start to make our way back to work, many of us are facing the discouraging outlook of a year or more of lost time in our careers. Most of us will have to take a few steps backward before we can go forward in rebuilding our professional confidence.

When I started my career I was excited: I’d wanted to tour since I learned that was an actual job and I was ready to hit the ground running. Instead, the ground hit me. I loved my crew and running shows and seeing the country, but there was a learning curve (like with any new job), and I was suddenly very much aware of just how much I didn’t know. Imposter Syndrome hit hard at that stage in my life and turned my learning curve into a confidence free-fall from my Summit of Stupid.

That voice monopolizes your attention when you realize you’re making someone wait while you finish a project. It whispers, “they’re right” when you’re told, “It’s not something I can teach you if you don’t understand it.” These little things build on each other and grow until you wonder how you were even hired in the first place.

I spent most of my time as an A2 caught in a loop: I felt horrible at my job so I figured I should quit, but I’d be just as horrible at anything else, so I should just stay where I was, but I felt so horrible at my job…. That cycle went on for years before I found a way out. There were days I was depressed and didn’t know why, but also days I went out with the crew after a tough load in and laughed so hard that I squeaked. Once I was told that my brand of book-smart intelligence was good for nothing more than being a “party trick.” Other times I had shows I mixed where everything clicked and I fell in love with my job all over again.

The even better news is this isn’t permanent. Imposter Syndrome is effective because it puts you on defense and instills a reactive state of mind. You no longer trust yourself to give an accurate assessment of your own skills. Instead, you take your cues from the words and reactions of those around you, and always give extra weight to the negative because it agrees with that little voice in your head. After all, why should you even try to improve when people who know so much more than you have told you you’re hopeless?

One of the best proactive moves I made was transitioning from an A2 to A1. Unknowingly, that was my final major step out of my Valley. Three years up the Slope, I was in tech for Saigon when a colleague told me he was worried that I didn’t realize how hard the show was to mix.

Reactively, my self-esteem would have curled up in the fetal position and that voice would have whispered what an idiot I was to think that I was even halfway decent at my job.

Proactively, I raised an eyebrow at a comment made out of stress-induced worry. After all, I’d spent as much time as I could working on my script, learning the show, and practicing the mix. While there would inevitably be a few mistakes, I had come prepared and I knew I could handle them.

Practicing proactivity gives you a solid foundation to approach a project or learn a new skill. And just like Imposter Syndrome, it starts small. It’s taking the time to relabel a cable instead of having to wrack your brain for its name every single load in. It’s refining the way you explain a project to the local crew so they don’t have to ask you to clarify the directions seven times. It’s signing up for a class or a workshop that the little voice says you don’t know nearly enough to attend.

These seemingly insignificant steps give you the building blocks for the rest of your career. Now, I’m particularly efficient at loading in and out shows because back then, in any proactive moment I had, I made one tiny tweak after another. Sometimes it was looming the end of a cable bundle a different way or even making a whole new loom for a special project. Other times it was pre-marking a tape measure to make instructions less complicated or taking pictures of an efficient case pack so it was easier to duplicate. Bit by bit the small fixes accumulated to make me more efficient, clearer, and more consistent.

Even after two years on my way out of my Valley, it wasn’t until the tech for Saigon where it actually hit home that I didn’t feel like an Imposter anymore. That month was challenging to say the least, partly because I was faced with many of my former triggers: not having all the answers, people getting frustrated, negative comments, and more.

That voice started whispering again, but when it did, I realized that I hadn’t heard more than a momentary peep from that insidious little thing in all of my previous two years as an A1. Without those triggers, that voice couldn’t sustain itself.

At that moment, I had the choice to drudge up my old, reactive habits or stick to my new, hard-won, proactive ones. Tech was still tiring and stressful, but I was better able to identify and mitigate my triggers. I did my best to address problems and solve what was in my control or ask for help with what wasn’t. If someone got frustrated I did my best to talk with them to see if there was an underlying issue. There was no way to avoid every frustration, but I could make sure I didn’t add to them unnecessarily.

If you find yourself with your own negative little voice, practice being proactive whenever you can. Even if it seems like it’s pointless, do it. One baby step at a time. Also, make a point to keep mementos. Did you have a great day, mix an amazing show, solve a tough problem? Write it down. When someone sends you a note or text or email telling you how amazing you are, save it, screenshot it, flag it. If you have a bad day, pull those out to remind you that this is temporary.

Lastly, find your kindred spirits: people who aren’t afraid to be honest when you need a swift kick, but will always have your back. (It helps if they work in the same industry and understand your world.) Mine are my former A2’s, current dear friends, and the very people I ask to proofread everything I send to this blog.

Rachel, Mark, and Dan were with each with me for a year of my first three tours while I navigated a new chapter in my career as an A1. Touring with someone creates a unique bond in itself, but each of these three have gone well above the call of duty time and time again to offer support, help, and motivation anytime I’ve needed it.

It’s not an easy road out of Imposter Syndrome, but the only way out is through. Keep in mind that you are not alone, grab a friend, and do your best to get a little better, one baby step at a time.

Article by SoundGirl: Heather Augustine

Another great article by SoundGirls: Confronting Bad Behavior as Women in Sound

Follow SoundGirls on Instagram, Twitter

The mission of SoundGirls.org is to inspire and empower the next generation of women in audio. Our mission is to create a supportive community for women in audio and music production, providing the tools, knowledge, and support to further their careers. SoundGirls.Org was formed in 2013 by veteran live sound engineers Karrie Keyes and Michelle Sabolchick Pettinato and operates under the Fiscal Sponsorship of The California Women’s Music Festival, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization. In 2012, Karrie and Michelle participated in the “Women of Professional Concert Sound” panel at the AES Conference in San Francisco. The panel was hosted by the Women’s Audio Mission (WAM) and moderated by WAM founder Terri Winston. Terri brought together five women working in live and broadcast audio. The groundbreaking panel (which also included Jeri Palumbo, Claudia Engelhart and Deanne Franklin), provided young women and men a glimpse into life on the road, tips and advice, and a Q & A with the panelists. More importantly though, was how incredibly powerful the experience was for the panelists. We had all been in the business for 20 years or more, yet most of us had never met before that day and within minutes we bonded like long-lost sisters. We were struck by how similar our experiences, work ethics, and passions were and wondered why our paths had never crossed and how our careers would have been different had we been there to support each other through the years. Each of us are strong on our own, but together we were even stronger and a powerful force. We were empowered. Each of us had been asked hundreds of times in our careers: Are there other women doing sound? How did you get into sound? How would a young woman go about getting into sound? Through creating SoundGirls.Org, we hope to establish a place for women working in professional audio to come for support and advice, to share our success and failures, our joys and frustrations, and for empowerment and inspiration.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.