The Theatre Backpacker

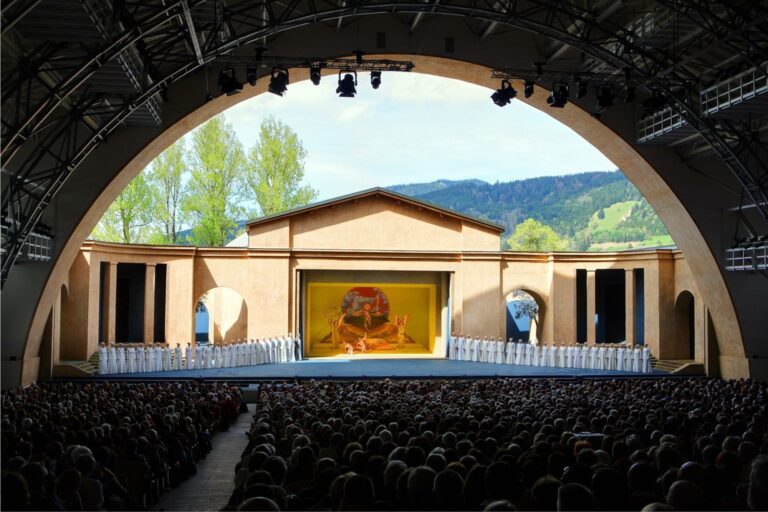

OBERAMMERGAU PASSIONSSPIELE: EXPLORING A SACRED THEATRE

By Jack Paterson | Part 1 of 10

PROLOGUE:

Date: November 2022

Location: Bali, Indonesia

It’s oddly cyclical that I finally find the time to start this article about a passion play in the Bavarian alps while on a cross-cultural Exchange project in Bali. Like many I suspect, I have found myself overwhelmed as theatres opened back up following the Covid-19 closures. As an artistic leader in London said to me: “too many things to do, and not enough time to do any of them well”.

Covid-19 impacted everybody everywhere. And although it can’t compare to the loss of life, family or friends, for anyone in the live performing arts – it was devastating. For independent artists like me whose opportunities turned out to often be far from home, whose artistic and therefore personal identities were tied to meeting new people, learning new approaches and perspectives… well, I still don’t know how to describe it.

We did our best through digital media; we stayed in touch on WhatsApp and Facebook and the rest. But with all the Arts Abroad funding cut in Canada at a time when it felt most vital to reach out and understand other people’s experiences in other places during this global trauma, it was as if we were denied even the chance to dream.

Yet here we are in a different world. After 2 years of discussing how we will all come back better, take more time, be healthier in our practices – it feels as if we just stepped on the gas.

I shouldn’t complain. In 2021/22, I was able to direct two shows in my hometown of Vancouver – something I’ve not had the opportunity to do since 2016. I am incredibly proud of the work on both shows and the teams involved. Additionally, an access driven international exchange and a research lab I had been trying to make happen for years received funding.

Back out on the road, I find myself retracing steps on the pre-Covid footpath. To see who’s still out there and maybe make some theatre together, to see old friends again, to see once bare streets of distant cities full again, to walk in amongst the architectures and sounds of places where I can’t speak the language again. Italy to Germany and back again, sojourns to Montreal and multiple towns in Ontario, and then back out internationally to Ireland, Northern Ireland, Eastern Germany, to England and now finally back to Bali in the first part of a collaboration with the remarkable Sanggar Paripurna

I remember someone back at theatre school (Circle in the Square, NYC 1996-99) saying that theatre was the replacement of human sacrifice in western society. I don’t know if this is true or not, but it stuck with me. “What aspects of humanity are we offering up to the gods? And what can we learn by doing so?” are questions I ask myself on every show. So, when I learned of the Balinese performing arts and its deep connection to spiritual beliefs and ritual, I was fascinated.

Virtually every form of music, dance, drama and puppetry has its origin as a function of ritual. Practices such as wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) reach back thousands of years. Even contemporary forms have a strong link to the past. Art is deeply connected to Bali-Hindu spiritual beliefs and cultural practice. In fact, there was no word for art in Balinese culture until introduced by Europeans in the 1930s. Art was simply part of life.

If Eastern European artists documented the science of creation in live performance and theatre, and the Americans documented the phycology, then the Balinese have followed a spiritual path.

I could imagine different yet similar elements in pre-Christian villages in Europe and the UK. What offerings, rituals and forms of mask, movement, puppetry, and storytelling could have endured the coming of Christianity and still inform western practices today? Surviving by adapting to Christian pageantry and mystery plays, evolving under Shakespeare, only to be severed from memory in English language culture by the Puritans and Cromwell. What performance practices still exist today in western societies that connected to the spiritual and to community?

I was raised to be a skeptic. But I am also an artist who works in the theatre, a realm of imagination. Despite my atheism, I maintain a healthy respect for the theatre gods and a vital belief in magic.

In pre-pandemic 2020, while visiting a friend in Munich, I learned of the Oberammergau Passionsspiele performed every 10 years since 1634 by the inhabitants of a Bavarian village in the mountains. I also learned that it was taking place that year and that the director, Christian Stückl, was based in Munich. I promptly headed down to the München VolksTheater – an innovator in the German state theatre scene and where Stückl serves as Artistic Director– and made myself a nuisance to the staff every day for two weeks until someone provided me with the contact information for whomever it was I needed to speak to to in order to observe rehearsals.

A flurry of friendly emails, a letter of invitation, and a grant rejection later, I still had enough money in my bank account such that if I was creative enough in my living – did a little vagabonding– I could pull it off.

And then Covid came.

I had completed a project in Italy with my friends Carolina Migli and River Coello. We were making small strides in applying cross sensory translation and active access design to international devised creation with Global Hive Labs and Teatro Trieste 34. Following the Alantide project, I visited Munich for a couple weeks. I remember my friend there saying, “What do you think about this Italy thing?”. I’d shrugged it off. I wasn’t really paying attention to the world. I was busy trying to find the cheapest but least insane Flixbus ticket to London, for the next Global Hive Labs. project and to see my youngest sister and her brand-new baby.

Then the Italian border closed, and it began to feel like portcullises were coming down behind me. The 6 am passport check at the Chunnel was held up as computers updated and the UK customs officers figured out the new protocols. In London, we updated and remounted The Medusa Project UK at the Cockpit Theatre, led by Katie Merritt of fusion theatre. Katie was ill after opening, but it turned out just to be the usual director flu that follows weeks of intensive activity.

Boris Johnson’s remarks in the media however left me less than comfortable with the UK’s approach to what was seeming increasingly to be a very serious situation. I had some people to see in Ireland. If things got really bad, at least I would be in Europe.

With my next few projects in Germany and flights home and back beyond my budget, my plan had been to do some backpacking, write some grants, catch up on a translation, and hopefully pick up some work at the hostels along the way.

I was in Dublin when St Patrick’s day was postponed and the theatres closed. The last show I saw before the pandemic was an independent matinee at Dublin’s The New Theatre. I was in Galway when the hostel told us they were shutting down at the end of the week. St Patty’s day was officially cancelled but the hostel kids celebrated on the new date anyways. Someone’s traditional dance had the only contact between partners being kicking each others’ feet from a distance. Strangers could still dance and laugh together for now.

Then Justin Trudeau came on the airwaves calling us all home. With health insurance and any potential future work opportunity in Europe in doubt if this went on too long, and my elderly parents back in Vancouver, I found a last-minute cheap flight and flew home.

I shouldn’t have been so nonchalant about that “Italy thing”. The Italian team I had worked with were in Piacenza – in the heart of the Lombardy region – where Covid first hit Europe like a fist. Despite all they were going through, conversations with Carolina via Facetime kept me going artistically for the most of the first year of lockdowns.

For two years, I ran a series of inter-provincial Canadian and international digital projects ranging from new translation development to international devised creation, doing my best to keep connecting people across distances and languages, and putting a few dollars into as many artists’ pockets as I could. Ironically, I’d had a grant proposal for research into long distance live collaboration through technology rejected a month before lockdowns began. The feedback had been “Why would anyone want to do this?”

In Vancouver, my most important job was being an uncle. My middle sister and her husband lent me a room at their place and I brushed up my Dungeons and Dragons, watched Avatar The Last Airbender, and made Lego spaceships with two of my most favorite people in the world.

And now here we are. As Carolina’s mother put it, “two Christmases and an Easter” later. In a new world – pretending like it’s the old one.

Tonight, I am observing I Made Sidia’s rehearsal process at Sanggar Paripurna.

The company is preparing a show for the upcoming celebration with over a hundred dancers and puppeteers. An innovator in Balinese performance but also a champion for his island’s traditions, Made’s work engages all members of the community from children to seniors. It is also a family affair. His brother and he have a deep artistic collaboration. On this project his brother is leading the gamelan orchestra and doing the voice work. His daughter, Ari, a recent graduate of ISI Denpasar and someone who will soon have a significant artistic presence, is one of his main assistants. His son, Sugi, is hunched over a computer preparing the media. There are over a hundred and fifty local community members engaged in the project. I have written about I Made Sidia before (linked below if you’re curious).

Perhaps because I’m watching an intergenerational creation with over a hundred community members, or perhaps because I’m watching a known innovator who values the traditional and sacred as well as the new, it seems right to write about another director, another ritual, and another village far from the Balinese sun.

Next: ARRIVING AT THE OBERAMMERGAU PASSIONSSPIELE

Links:

Article: In Search of Taksu 3: Bridging Cultures & Past and Present in Balinese Performing Arts

Francophone New Writing: An Interview with Festival du Jamais Lu

In Search of Taksu 4: A Conversation with Professor I Wayan Dibia

Jack (he, him) is an award-winning devisor, director, translator, and creative producer whose work and practice have taken him across Canada, Europe, the United Kingdom, and around the world. Projects have ranged from contemporary devising, multi-disciplinary, cross-cultural, and multi-lingual experiences to new works & texts, contemporary approaches to classical theatre and main stages. Shows under his direction have garnered over thirty theatre award nominations with many wins. He trained at leading international theatrical institutions including Circle in the Square (NYC, USA), GITIS The University of Performing Arts (Moscow, RU), ISI Indonesian Institute of the Arts (Bali, INA) and received his Masters in Fine Arts from the renown East 15 Acting School and University of Essex (London, UK).

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.