The very commonly seen “pike arch” and rib flared handstand is something many gymnastics coaches and athletes are frustrated by. Although to the average person it may not seem like a big issue, in reality to the trained coach or medical provider it is known to be something that can haunt a gymnast for many years if not corrected. From a performance standpoint, perfect handstand alignment and body shaping is the fundamental ground layer to all high-level skills. Gymnasts must learn and continuously practice this basic handstand to progress.

From an injury prevention standpoint, a non – stacked handstand position that shows this rib flare/pike arch often places excessive stress on a few joints. Very commonly gymnasts who have this habit and progress further in the sport begin to complain of lower back pain, shoulder pain, and wrist pain. Although many people jump to a drill or hands on cue for fixing it, we have to remember to take a step back and remember there are many causes that may contribute to what appears to be the same problem. Rushing to fix it without considering all of the possible contributing factors may create more headaches and limited progress. To help with this, I wanted to share 6 common reasons I find in gymnasts I work with and how to address them.

Believe it or not, this is way more common than people may think, both in younger and older athletes. We have to remember that there are normal adaptations to certain sports with more training. The lat, teres major, and pec muscle groups are extremely important for dynamic shape changing, maintaining compression in skills, and higher power development in gymnastics. With that said, we do not want these muscles to become so overdeveloped they limit mobility in other planes of motion, like overhead shoulder motion needed in many gymnastics skills.

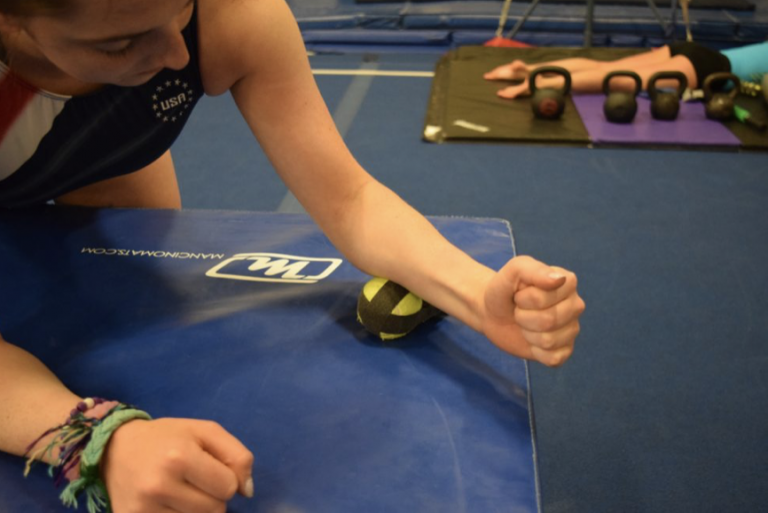

More specifically discussing the lat muscles, they originate from the lower back region and attach to the inside of the arm bones. When the lats become very stiff from training, they can easily overpower the core’s ability to keep the ribs from flaring when the arms must move fully overhead. Insert a very common fib flared handstand that no matter how you cue the athlete or coach them through drills, it never disappears. The teres major is another common culprit, and when excessively stiff it often creates excessive sideways scapular movement when the arms must go fully overhead. I recommend everyone screen gymnasts’ isolated overhead motion, address soft tissue as needed, build control/strength in the new range as it is gained, and then stress proper technique progression so it transfers to skill work.

Closely related to the same concepts as above, gymnasts are prone to get stiff in their quad and inner thigh muscles (adductors) simply by practicing good form all the time. Straightening your legs and squeezing them together for many hours per day, week, and year can quickly create limited soft tissue mobility. Not to mention the huge quad and hip flexor demand gymnastics skills naturally place on athletes. Along with reducing split/leap/stalder range, this excessive stiffness also may pull an athlete into an anteriorly tipped pelvic position with internally rotated hips. This may look familiar to the pike arch handstand position. The two points above can feed off each other in a “chicken or the egg” type relationship and an argument could be made either way. The takeaway message is that daily soft tissue work and properly targeted mobility stretches are essential if you want to kick the bad pike arch handstand habit.

In another overlapping type principle, often times gymnasts have large muscular imbalances that exist. The most common examples include having lots of horizontal pushing (pec, triceps) strength, but not an equal amount of horizontal pulling (middle/lower trap, posterior rotator cuff) strength. In the lower body, lots of anterior hip and adductor strength is often seen with a large imbalance of missing glute, hamstring, and external rotator strength. The limited posterior chain strength may not show up in basic gymnastics movements, but more so in faster or higher force situations.

These imbalances can feed both the ongoing positional hip and shoulder faults noted above, but they also may create a situation where a gymnast can not create co-contraction around their hips and shoulders to create a flat lined handstand. It’s important that we program strength to have a general base of strength in all 3 planes and then build in sports specific components as the next layer.

To combat this issue and combat many common injuries, I be sure to program a lot of horizontal pulling within our strength work. This includes dumbells Y/T’s, side lying external rotation, half kneeling band “U”s, renegade rows, weighted horizontal rows, and more. There are many more good exercises beyond these, but just be sure to plan for it.

Sometimes there isn’t a more complex biomechanical or technical issue. It could honestly be that the athlete just isn’t strong enough yet to handle high force skills without breaking alignment. Younger athletes that are still developing often show this issue. Many of the skills performed in gymnastics in support, moving through a dynamic push-up/handstand push-up, or in relation to blocking require a lot of upper body strength, control, and dynamic stability. They also require a ton of anterior core strength and breathing control to maintain the depressed rib position.

It requires a lot of prime mover strength in a heavy eccentric fashion, but also a lot of strength from the smaller stabilizers of the shoulder joint. If an athlete is able to show the fully flat handstand shape we want in an unloaded position but not during skills, it may be a matter of programming more upper body closed chain positions to help build their capacity. It could also be a learning curve in the technical department, which leads into the next point.

On the other side of the coin, in older gymnasts who have spent a lot of time gripping, it is very common to see their forearm muscles start to become stiff. This is usually more common in male gymnasts than female gymnasts. If this occurs, the gymnast may not have the appropriate weight bearing wrist extension to stack their handstand properly. It may create what looks like a closed shoulder angle or piked hip angle, as the body is trying to maintain balance from falling over. I recommend people screen the wrist for at least 100 degrees of motion, and then if limited do some soft tissue work to the forearm.

Although strength, biomechanics, movement assessments, and fundamental capacity are important there is also a huge role here for technical and progression mastery. I think that as a whole many people underestimate just how much work and time it takes to master even basic weight bearing skills like static handstands. There is a ton of grunt work and dedication that comes with trying to really master the handstand position and use it well in swinging, tumbling, vaulting, or other gymnastics skills.

As coaches and medical providers looking at athletes who struggle, don’t be afraid to not make a situation more than it is. If someone lacks strength from above or technical mastery as noted, having a professional discussion with the athlete and helping them create a game plan is the correct step. Choose 2 or 3 good ones that are appropriate for the gymnast, then in a circuit make the athlete completely master them to see progressive changes.

The reality of working in gymnastics is that fatigue or lower motivation levels to make corrections is part of the equation. I have worked with my fair share of athletes who simply don’t follow the directions or amount of dedication it takes to execute handstand shaping drills correctly. Other gymnasts may be on the other end of the spectrum, constantly having their foot on the gas pedal not understanding that more is not always better. They may fatigue by the end of a workout or week, leading to limited energy and ability to maintain perfect shapes. Intelligently training in fatigued states to mimic competition clearly is needed, but there is a fine line that exists between that and allowing poor movement habits to creep in. That’s where the art of coaching comes in, as I’m sure many readers would agree.

I hope that this post has given people some more ideas about how to critically think about this common issue within our sport. There are more ideas I think go beyond that, that I have learned from some great coaches, but for now I wanted to focus on what I thought were the most common. Best of luck!

Published in collaboration with Shift: Movement Science and Gymnastics Education

Dave Tilley DPT, SCS, CSCS is a Physical Therapist who graduated in 2013 from Springfield College. Dave comes from an extensive gymnastics background, being a former athlete and currently still coaching optional level gymnastics in Boston. Dave was a competitive gymnast for 18 years, 4 of them collegiately as part of the Springfield College Men’s Team. Dave has also been coaching gymnastics for 12 years, being involved in beginner, national, and elite levels. His unique background as a former athlete and current coach gives him a one of a kind approach for the performance and rehabilitation of gymnasts. He has successfully treated some of the most talented high school, collegiate, and junior elite level gymnasts in the country. Along with gymnastics, Dave enjoys treating athletes of all sports as well as the specialized treatment of Olympic Weightlifters and CrossFit athletes. He has worked with regional and national level Olympic Weightlifters, as well as Regional and Games level CrossFit Athletes. Dave graduated from Springfield College with his Bachelors in Science, a Minor in Psychology, and Doctorate in Physical Therapy. He became Board Certified in Sports Physical Therapy in February of 2016, and became a Certified Strength and Conditioning Coach in 2017. His current interests include prevention and rehabilitation of extension based spine injuries, shoulder and hip instability, periodization and strength and conditioning models, as well as the science involved in long-term athletic development, mobility training, and motor control. He participates in ongoing continuing education by attending various courses, collaborating with other professionals, and staying up to date with the most current medical research. Along with treating in the clinic, Dave is also the CEO/Founder of “SHIFT Movement Science and Gymnastics Education”. This company was started in 2014 to help educate those involved in gymnastics, medical fields, Olympic weightlifting, CrossFit, and more about optimal performance and preventative rehabilitation strategies. By combining his roles as a healthcare provider, current coach, and athlete Dave looks to help remold the gymnastics world with current, scientifically backed principles that optimize a gymnast’s long-term potential. His new forward-thinking ideas have been nationally recognized with members of USA Gymnastics, being implemented into JO, Collegiate, and Elite level programs. Dave travels to speak both nationally and internationally at various events across the country including Make It Right Elite Gymnastics Camp, USAG Regional, and National Congress, Power Monkey Camp in Tennessee, and has consulted with many NCAA Division 1 Men’s and Women’s Gymnastics. Dave is very passionate about his work both in the clinic and gymnastics training arena. He aims to deliver the best possible care to the clients he sees and athletes he trains. He hopes to soon become more active in the role of conducting research studies related to gymnastics. Dave is the newest addition to the Champion Physical Therapy and Performance Team.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.