By executive order, President Donald Trump recently rescinded the three-year-old rule that requires the Director of National Intelligence to disclose the number of civilians killed by drone strike outside of official war zones. What could this news possibly have to do with me, a composer/playwright?

Only that it reinforces a point I’ve been making in my current project, Drone—a play about the devastating human toll that our Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) program is taking on the world. In the play, the main character, Mike Powell, a drone pilot who has just accidentally killed innocent people says:

“When the victims aren’t high-level militants, no one bothers. Our government will release no information. It would make us look bad. No one will even mention their names in the press. They’re just bugsplats. The killing will go on on both sides. Does anybody care? No one questions it. For us, they never existed.”

A news item is what drove me to this particular subject in the first place—an article in The Intercept that was based on leaked CIA documents about drone strikes. The documents demonstrated that in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Somalia, nine out of ten victims are not the intended targets, and many of the remaining targets have been mistakenly identified through incorrect metadata, poor intelligence, and by paid informants who seek revenge or who derive personal gain from identifying innocent targets. (The avaricious revenge-seeker became a plot device I eventually used in my play.)

Even the CIA admits the program is questionable as to its effectiveness, that it “may increase support for the insurgents, particularly if these strikes enhance insurgent leaders’ lore, if non-combatants are killed in the attacks, if legitimate or semi-legitimate politicians aligned with the insurgents are targeted, or if the government is already seen as overly repressive or violent.”

President Obama expanded the controversial signature strikes in which people are targeted, not on the basis of specific evidence, but rather on their behavior. One of the invidious results of this policy led to the administration’s sweeping edict that “all military-age males in a strike zone are combatants.” The drone-warfare issue is more relevant today than ever under Trump, who has inordinately upped the ante, killing as many as thirty percent more innocent civilians, though this receives virtually no media coverage. Upon viewing a drone strike, Trump asked the CIA operative why we waited to strike a combatant until after he left his family’s home and was a safe distance away. During his campaign, he announced, “When you get these terrorists, you have to take out their families.”

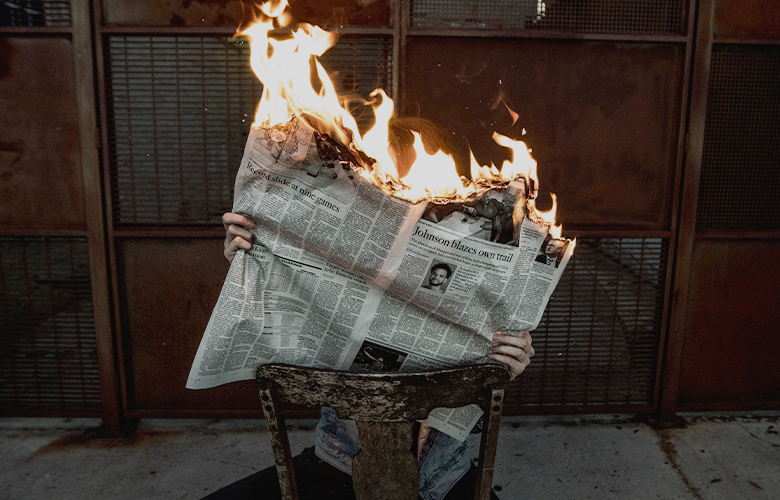

Because of the mainstream media’s virtual blackout on the subject, the American public remains in the dark about UAV attacks. As a result, most Americans blindly support the program. Trump’s executive order serves to keep not only the public but also our elected officials ignorant of the human cost of our actions.

We writhe from the gun violence within the United States, without the slightest awareness that our violence abroad encourages and abets the violence here.

The public has bought into the myth that the UAV program protects us against terrorists at a minimal cost to American life—no boots on the ground. The government, in consort with the media, has prevented the public from ever seeing the photographs or videos of the horror perpetrated on people by these drone strikes. During the Vietnam War, the horrifying photos in the news played a large role in turning the public against the war. In contrast, most of the drone footage, which appears on the internet, glorifies the practice by showing how efficiently our technology can blow up an evil and faceless enemy. These videos, which are termed “war porn” turn the strikes into entertainment and are viewed by more than ten million people.

But how to turn this repugnant practice into a compelling dramatic work? Nothing will turn off audiences and critics faster than didacticism or agitprop. I’ve used the political in many of my past works. In Ye Are Many—They Are Few, Cantata for a Just World, I concentrate on public apathy and the insidious effects of tribalism. Even in my Dorothy Parker musical, You Might as Well Live, I give Mrs. Parker a more serious weight than she is generally afforded by highlighting her impassioned hatred of racism and her support of socialism. But never had I addressed so specific a problem as the drone program. I felt stumped.

I found the solution to the problem when I read about the men and women who operated drones. Their stories embodied an inherently dramatic force. In many cases, drone operators surveil their intended victims for weeks, before they strike them down.

In that process, they come to know their targets almost intimately, often developing a sort of sympathetic, though one-way, relationship with them. Thus when they are finally asked to bomb them, it’s tantamount to killing someone they’ve known for some time. The results are devastating for both sides. Here then was my drama.

Many films (Eye in the Sky, Good Kill, Drone) and a play (Grounded) have dealt with the issue, but only from the perspective of how the American participants are affected, rendering those dramas one-sided and emotionally distancing. I felt it necessary to show the human cost on both the perpetrators and the victims. The pilots must view the mutilated bodies after they strike, something their real-pilot counterparts don’t contend with. Further there is the guilt of killing others with no risk to oneself—having “no skin in the game.” Thus people involved in the program suffer PTSD, as well as “moral injury.” On the other hand, the victims and their families, even before their horrible deaths, are subjected to the constant humming noise of the drones, making them unable to sleep or concentrate. The continual threat from above poses debilitating psychological damage on a whole society.

My solution was to depict two parallel families: Mike, an ex-fighter pilot who becomes a drone pilot in Nevada to be nearer his physician-assisted wife and his sixteen-year-old soccer-playing son; and Salar Khan, a miner who lives in the tribal areas of northern Pakistan with his subservient wife, his aging mother, and his sixteen-year-old soccer playing son.

Mike watches Salar, his wife, son, and mother having tea, dancing, and praying. He even watches Salar and his wife making love. The daily observation leads to a voyeuristic identification and admiration of the Khans, despite the warnings of his trigger-happy, gung-ho co-pilot, Tonya. The daily surveillance and Mike’s participation in bombing a school and a hospital have devastating moral and psychological effects on both families. Unlike fighter pilots, whose bombing is barely noticeable as they fly away from their targets, drone pilots are confronted with viewing on a screen and making accounts of the maimed bodies they have just killed. The psychological damage from this is unfathomable. When the people you have just killed are people you’ve been observing for weeks, the results are even more devastating.

One of my goals was to give the Pakistani family a real life that we could identify with. When the family is severely rattled as they realize that a drone may be surveilling them, the grandmother laments on what both the Taliban and the Americans have done to their world:

“How did we become the enemies of the world? What do we have to do with their war, their revenge? We’re not even human to any of them. We lived in peace. We were a happy people. Now Arman is afraid to go to school. Women used to be treated with respect. Now Diwa can’t sell her lovely embroidery at the market. We are warned not to vote, not to visit a male doctor even when we are very sick, our girls can’t go to school. We are told what to wear. Not allowed to leave the house without a man. It’s destroying our families. No one trusts anyone now. When you were young, Salar, people were not afraid to visit each other. Neighbor did not inform on neighbor. There was honor. No one dares to go out at night anymore. We had a culture—our own culture—a real culture and it was beautiful. Now we have fear and mistrust. We are no more than the ghosts of our former selves. Looking on at a life that doesn’t exist any longer. I want the woman I was back. I want the life we lived back. I’m glad I don’t have much longer in this world.”

“The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity,” wrote William Butler Yeats, a statement, I believe, that characterizes the paucity of response by serious artists to the universal injustices of our time. Although this seems to be changing since Trump’s election, artists need to play a larger role in the discussion of today’s crucial issues.

Sadly, funding sources are reticent to back controversial projects and audiences would rather be entertained by inanities than challenged in their long-held beliefs.

Historically, artists have often played crucial roles in the social issues of their times. Three examples come to mind: Beaumarchais’s drama, as well as Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto for Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro played a role in fomenting the French Revolution; Picasso’s “Guernica,” helped raise funds for Spanish Civil War refugees; and Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem was his passionate plea for peace. Today’s artists would do well to follow these examples and help refute the erroneous notion that art no longer speaks to the great issues of our time.

About Norman:

Norman Mathews is a composer, playwright, and author. His works have been seen at the Kennedy Center and at venues around the world. His opera La Lupa was showcased at the Fort Worth Opera Company. You Might as Well Live, his musical about Dorothy Parker has been performed by Tony-Award-winner Michele Pawk and Broadway luminary Karen Mason. The Wrong Side of the Room: A Life in Music Theater, Mathews’s autobiography, was recently published by Eburn Press.

Pushing Boundaries with Art: How Far is Too Far?

Do We Need Protest Art Now, More Than Ever?

Norman Mathews is a composer, author, librettist, and playwright. His work has been performed at the Kennedy Center, on radio, and at theaters and concert venues around the world. He is a recipient of numerous awards, foundation grants, and commissions. His play, "Drone," has just been selected as a semifinalist for the Dayton (Ohio) Theater's Future Fest to be presented July 2019. In his younger days, Mathews was a dancer-singer-actor on Broadway and film. He has worked with Dorothy Lamour, with Barbra Streisand and Gene Kelly in the film version of Hello, Dolly!, and with Michael Bennett. As a composer-playwright, his award-winning musical about Dorothy Parker, You Might as Well Live, has been performed by both Tony-Award-winner Michele Pawk and Broadway star Karen Mason. The piece has been seen at Chicago’s Harris Theater of Music and Dance, the Orlando Shakespeare Theater, and the New York Musical Theater Festival. La Lupa, his opera based on the Giovanni Verga novella, was recently showcased at the Fort Worth Opera Company. Ye Are Many—They Are Few, Cantata for a Just World, for four singers and piano, received a Puffin Foundation grant and was premiered at The Chicago Cultural Center by the acclaimed vocal group, Vox3. Sonnet No. 61 (part of a 3-sonnet cycle to Shakespeare, entitled Love’s Not Time’s Fool for mixed choir, piano, and oboe and flute obbligato) was the winner of the American Composers’ Forum 2011, VocalEssence Award. His song cycle, Songs of the Poet, settings of Walt Whitman poetry, had its European premiere at by Gregory Wiest, an American tenor with the Munich Opera, who recorded the work for Capstone Records (CPS 8646). The work was later performed at the Kennedy Center. Rossetti Songs, a cycle of five songs set to Christina Rossetti poetry for mezzo-soprano, piano, flute, and cello, was recorded by Navona Records (NV5827) and distributed by Naxos. It was recently broadcast on Public Radio. Mathews’s cabaret music has been performed by Tony-Award-winner Debbie Gravitte and Tony-nominee Liz Callaway. His autobiography, The Wrong Side of the Room: A Life in Music Theater has received unanimous critical praise. As a journalist, he has been News Editor of Dance Magazine, Managing Editor of Sylvia Porter’s Personal Finance Magazine, and Editorial Director of Merrill Lynch internal publications. His articles have been published in Common Dreams and the Times of Sicily. His music is published by Graphite Publishing. Mathews holds a B.A. and an M.A. in music from Hunter College and New York University.

Read Full Profile© 2021 TheatreArtLife. All rights reserved.

Thank you so much for reading, but you have now reached your free article limit for this month.

Our contributors are currently writing more articles for you to enjoy.

To keep reading, all you have to do is become a subscriber and then you can read unlimited articles anytime.

Your investment will help us continue to ignite connections across the globe in live entertainment and build this community for industry professionals.